Categories: transparency • access • location • inform • provide

Privacy dashboard

Context

A service (or product) which processes personal data of users may make that data accessible to them. This is often the case whether conforming to laws about self-determination and notice, or merely wanting to provide an additional privacy consideration for the sake of users. The controller concerned wants to open up about the data they have processed, and to improve the ease of use for configuring privacy settings.

Problem

A system should succinctly and effectively communicate the kind and extent of potentially disparate data that has been processed.

Users may not remember or realize what data a particular service or company has collected, and thus can't be confident that a service isn't collecting too much data. Users who aren't regularly and consistently made aware of what data a service has collected may be surprised or upset when they hear about the service's data collection practices in some other context. Without visibility into the actual data collected, users may not fully understand the abstract description of what types of data are collected; simultaneously, users may easily be overwhelmed by access to raw data without a good understanding of what that data means.

Forces and Concerns

- Controllers want to provide users with sufficient information to determine how it is used, and to prevent regrettable sharing decisions

- Controllers want to prevent both over and under-sharing, so as to provide users with the best experience possible

- Users often do not realize the privacy risks in providing their personal data

- Users do not want to be subjected to too many or overly detailed notifications, as they will quickly make a habit of overlooking them

Solution

Provide successive summaries of collected or otherwise processed personal data for a particular user, representing this data in a meaningful way. This can be through demonstrative examples, predictive models, visualizations, or statistics.

Where users have choices for deletion or correction of stored data, a dashboard view of collected data is an appropriate place for these controls (which users may be inspired to use on realizing the extent of their collected data).

[Structure]

A variation of the privacy dashboard, Privacy Mirrors, focuses on history, feedback, awareness, accountability, and change.

[Implementation]

Implementing this pattern is a matter of providing logging, reporting, and other informational access and notifications on user-selected/filtered, appropriately defaulted, relevant usage data.

Aspects which the controller wishes to inform their users about may include the collection and aggregation of their data, particularly personal data which:

- changes over time,

- is [processed] in ways that might be unexpected,

- is invisible or easily forgotten, or

- is subject to correction and deletion by users.

Consequences

[Constraints]

As in other access mechanisms, showing a user's data back to them can create new privacy problems. Implementers should be careful not to provide access to sensitive data on the dashboard to people other than the [user]. For example, showing the search history associated with a particular cookie to any user browsing with that cookie can reveal the browsing history of one family member to another that uses the same computer.

Also, associating all usage information with a particular account or identity (in order to show a complete dashboard) may encourage designers to associate data that would otherwise not be attached to the user account at all. Designers should balance the access value against the potential [considerations within] Deidentification.

Examples

Google Privacy Dashboard

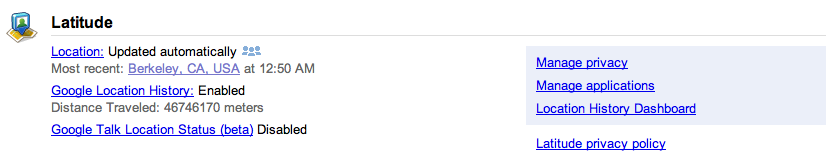

The Google Dashboard shows a summary of the content stored and/or shared by many (but not all) of Google's services (Latitude, Google's location sharing service, is shown above). For each service, a summary (with counts) of each type of data is listed, and in some cases an example of the most recent such item is described. An icon signifies which pieces of data are public. Links are also provided in two categories: to actions that can be taken to change or delete data, and to privacy policy / help pages.

Google Accounts: About the Dashboard

See Also

Dashboards are a widely-used pattern in other data-intensive activities for providing a summary of key or actionable metrics.

[Related Patterns]

This pattern complements Awareness Feed. As this pattern provides collective summaries of processed data, and Awareness Feed keeps users informed of such data, as well as what can be derived, they can work together. In doing so, users are better equipped to take actions which are in line with their personal privacy preferences.

This patter is similar to Privacy Mirrors. They have overlapping contexts, describe overlapping problems, and have solutions which have similar elements within them.

This pattern uses Appropriate Privacy Feedback, as it empowers users to act on detail they have been drawn attention to.

[Sources]

N. Doty & M. Gupta, (2003). “Privacy Design Patterns and Anti-Patterns Patterns Misapplied and Unintended Consequences,” 1--5.

D. H. Nguyen and E. D. Mynatt, (2002). “Privacy Mirrors : Understanding and Shaping Socio-technical Ubiquitous Computing Systems', pp. 1--18.

S. Romanosky, A. Acquisti, J. Hong, L. F. Cranor, and B. Friedman, (2006). “Privacy patterns for online interactions,” Proceedings of the 2006 conference on Pattern languages of programs - PLoP ’06, p. 1.

C. Bier & E. Krempel, (2012). “Common Privacy Patterns in Video Surveillance and Smart Energy,” In ICCCT-2012 (pp. 610--615). Karlsruhe, Germany: IEEE.

E. S. Chung et al., (2004). “Development and Evaluation of Emerging Design Patterns for Ubiquitous Computing,” DIS '04 Proceedings of the 5th conference on Designing interactive systems: processes, practices, methods, and techniques, pp. 233--242.

H. Baraki et al., (2014). “Towards Interdisciplinary Design Patterns for Ubiquitous Computing Applications,” Kassel, Germany.

G. Iachello and J. Hong, (2007). “End-User Privacy in Human-Computer Interaction,” Foundations and Trends in Human-Computer Interaction, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1--137.

Corrections or additions? Contribute on GitHub.